I grew up in rural Oregon, among the trees. The forest was a source of creative inspiration for me, and sparked my passion for wood as a building material that was both beautiful and sustainable. It was also the source of economic livelihood for my neighbors, many of whom were loggers and millworkers. But when the timber industry contracted in the 1980s, the sawmill in my hometown shut down, and I remember vividly many of my schoolmates’ fathers losing their job. That experience wasn’t unique to us; it’s a story shared by rural communities across the west, and many have remained economically depressed to this day.

Recently, however, an exciting new realm of large-scale engineered timber products called Mass Timber has been gaining traction in the US. Not only does Mass Timber open up new possibilities to use wood for large-scale construction, normally achievable only with steel and concrete, it also has the potential to breathe new life into the old mill towns of the west, as the mills are being retooled to fabricate it. In fact, there are several high profile Mass Timber buildings on the way in Portland, supplied by DR Johnson in Riddle, Oregon, the first such domestic supplier, and more mills are getting their certification in the near future.

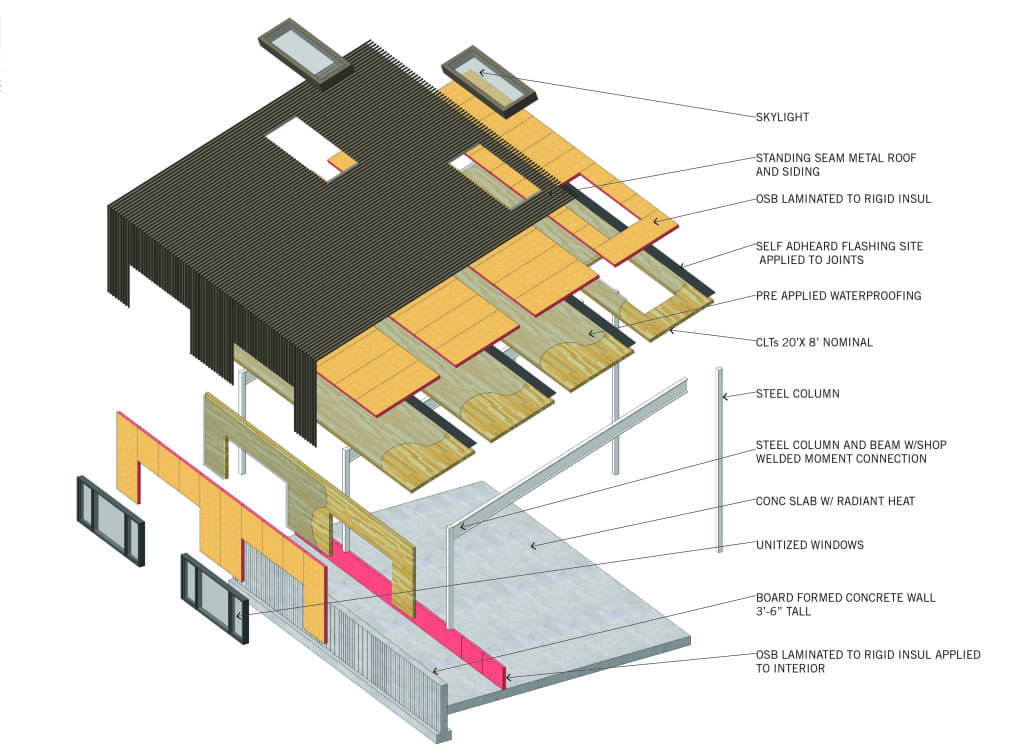

Mass Timber is an umbrella term which includes a number of large-scale manufactured wood members, the most exciting of which is Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT), essentially a laminated panel system, comprised of layers of small young-growth wood members, about the size of 2x4s, with alternating grain direction. The layers are glued together using processes similar to glulam fabrication, to create panels which are incredibly rigid and strong, in sizes up to 40 feet long and 12 inches thick. Think, “gigantic plywood”.

In conventional construction, walls, floors, and structure are normally comprised of a variety of smaller elements like beams, studs, flooring, sheetrock, and so on. CLT panels are so big and stiff, they can span great distances and serve as entire walls, floors, and structural elements simultaneously. The potential for “prefabrication,” where building components are fabricated in a shop to minimize expensive and disruptive on-site construction, is extensive. Buildings can be conceived of like an “IKEA flat-pack” kit, which can be efficiently stacked, trucked to site, and erected much faster than conventional construction. It’s also 5 times lighter than concrete, saving significant cost in foundations. The result is an incredibly pure and elemental expression of architecture, with the warmth of exposed wood.

Over the last century, for a variety of sensible reasons, the mandate to use concrete and steel for the structure of large scale buildings has been “baked into” our codes, regulations, and industry practices. Concrete and steel is strong, predictable in fire and earthquakes, and well-tested. But the truth is those materials are highly unsustainable and polluting; fabrication processes release millions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere each year.

The construction industry has made some great strides to acknowledge its role in the fight against carbon emissions and climate change. Elective standards for sustainable design such as LEED and Green Building Challenge have become mainstream, energy efficiency and the cost of renewable energy sources like solar continue to improve, and the development of “green” building products like natural carpets and formaldehyde-free plywood start to address the sustainability of building materials. However, those advances are largely skin-deep, and the pressure mounts to address the carbon footprint of the “bones” of our buildings, the structure itself. By replacing materials that emit carbon via fabrication processes—steel and concrete—with materials that sequester carbon—wood, after all, IS largely comprised carbon—the net reduction released into our atmosphere is compounded.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has recognized this potential, and recently hosted a design competition to further develop and test CLT and Mass Timber, awarding a $3 million grant to teams in Portland and New York City. The funds primarily go toward laboratory testing for the fire and seismic characteristics of Mass Timber, and the race to build the tallest wood building in the U.S. has begun.