“Work-life integration” is the latest term to describe the evolution of work-life balance, which can be described as blurring the boundaries between the once distinct professional, personal and family sectors of our lives. To accommodate personal and family commitments – and benefit from improved productivity and happy staff—flexible work hours have become commonplace. Teleworking has increased by about 80% since 2005 and that doesn’t even count the 38 million home-based businesses in the US. Working away from the office helps people manage personal, family and professional obligations more effectively—and it seems to be enlivening our communities as well.

As designers, we know the mantra “form follows function”. Today’s offices look like living rooms, cafés function as workplaces, and homes have multiple offices. We are even seeing modern day communes where a mix of professionals choose to live (and sometimes work) under one roof to spark new ideas, relationships and ventures. This mix is driven by advances in technology and a we-can-have-it-all mentality.

However, an integrated life isn’t an entirely new or high-tech concept. For more than a decade San Diego architect Teddy Cruz has been studying the shanty towns of Tijuana, Mexico where families adapt and grow their homes as needed and when needed. An extra unit might be built as a retail or restaurant space to meet the needs of the neighborhood. Later, the family may add another bedroom for their son and his new wife, or for a grandparent. The form and function of the space is adapted to the family’s demands at that particular time of life. The result is a micro-scale mixed use “ecosystem” where family, business, and neighbors each perform essential roles.

Estudio Teddy Cruz’s graphic diagram of the micro scale of mixed-use density in Mexico versus the sweeping single-use zoning of suburban San Diego and the disruptive effects of growing immigrant communities developing along the route to the city.

While this sort of flexible development is common in cities, where space is tight, land is pricey and there is density to support storefronts and restaurants even in predominantly residential areas; communities just outside urban cores are beginning to emulate this urban form. The resurgence of city living has injected density in the inner ring suburbs as well. Mid-day streets, shops and restaurants are busier as professionals who work remotely or are granted the freedom to take short breaks from the grind to address personal and family responsibilities. These blended lives require convenient locations and are driving up home values near shops, restaurants and transit. Developers are taking heed and building places that combine residential, retail and offices all at once.

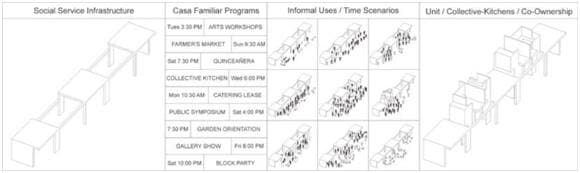

Estudio Cruz’s representation of various typologies that can become the building blocks of communities.

Cruz shares the shantytown lessons of organic growth and combined functions as a methodology for transforming the repetitious, single use, suburban developments in the sprawling areas of southern California. Cruz describes multi-use frameworks with shared infrastructure—like community-owned storefronts that rotate vendors and give residents a place to conduct business. These bottom-up micro-scale developments provide a basic yet adaptable framework for neighborhoods to introduce opportunities for local commerce and connections close to home.

Our increasingly blurry lives require environments that support an equally blurry mix of uses in our communities. It seems the suburbs may be taking a cue from the diversity of its neighboring urban centers and the distinction between the two is becoming less clear.